Dear Reader,

The following is a continuation of my blog series based on my book The Midnight Hour: A Jungian Perspective on America’s Pivotal Moment. If you are just now picking up on the series, you might start with the Introduction: Welcome to the Challenges of Change.

I hope that it will help you, as writing it has helped me, to find a candle to contribute to your light.

Whether you agree with me or not, I hope my work helps you clarify your own position, both within and to the chaotic times surrounding us. Above all, I hope it helps you create a new vision of the future and a new hope that draws you to commit to it.

Bud Harris

Asheville, North Carolina

The Midnight Hour:

A Jungian Perspective on America’s Pivotal Moment

Chapter 10: Health Care: Isn’t It Time to Quit Being the Cruelest Developed Nation?

How can I begin to write about my country — the country where I grew up, the country that has given me a lot, the country I love, that I am a patriot in — as the cruelest developed nation in the world? The only way I know is to begin with a story. This is the story of three generations of my family’s relationship to our healthcare system. These are stories of suffering, struggle, and grief. They molded the lives of my family members. But I’m not telling them as tales of woe. I’m telling them to show the human side, my experience, my family’s experience of the financial costs of healthcare, and the cross these costs crucify us on. And for the first time I’m going to let my inner deplorables—my shadow side, long repressed—speak on the page.

If you look around you, in your own family, among your friends, relatives, neighbors, colleagues at work, fellow church members, all the people around you, you will see plenty of stories like mine. In our addiction to positive thinking, we have let ourselves come to believe that being happy and healthy is normal. It is not. Chronic, acute, and temporary illnesses, accidents, and death are touching us all the time. Perhaps it is our denial that allows us to be so cruel. In my professional practice as well as in my personal life, I have grown very aware of how many people, often quietly, too quietly in our society, are suffering from intense illness, physical, psychic, and emotional pain, every moment of the day.

In 2016, a total of 2,744,248 resident deaths were registered in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control. Of those people 155,800 died of cancer. Cancer—there is no good way to die of cancer. It is a long, torturous, terrifying journey for patients, for loved ones, and often for caregivers as well. Accidental injury claimed 47,800 lives and caused many more serious injuries. While these statistics demand attention, our real attention must stay with the knowledge that they represent the deaths of real people—people who loved, feared, hurt, dreamed, hated what’s happening, and wanted to have whatever care and security they could get. And they wanted the same for their spouses, partners, children, loved ones, or even for the person in the next hospital or nursing home bed. They are people like those in my stories.

Story Number One

Shortly after World War II, when I was around ten, a vivacious baby girl was born into our family. She brought joy to the eyes of my parents and into all our hearts as we were starting a new life after the war. One afternoon she was sitting on the edge of our dining room table after a swim in her little two-piece swimsuit. Laughing and waving her arms, she entertained us and some family friends. Suddenly, my mother’s face became deadly serious. She had noticed a lump on my sister’s side that took the smiles off everyone’s faces.

Our friends stayed with us until our doctor arrived. Soon my sister was in the hospital and being operated on for a Wilms cancer tumor on her kidney. I was only a child at the time and it took me decades, until I was in my professional training, to imagine the ongoing terror that must have seized the heart of that little girl who had been cut open from her backbone to her belly button to have her kidney removed. But I could see the anguish in my parents’ eyes and the bitter tears they shed at night as they prayed for her life. Helplessly they had to watch their baby suffer and could not even cradle her in their arms for many days. There wasn’t much in the way of health insurance in those days, but my parents weren’t considering costs because action was needed. But the costs caught up with us. They hovered around us like a cloud, haunting our family, causing fear and stress until they were finally paid.

Story Number Two

Shortly after my sister’s recovery, my mother was diagnosed with breast cancer. Like so many women, she suffered a long, harrowing journey of multiple surgeries and crude (at that time) radiation treatments. She died a painful death in 1952 when she was forty-two. I was fourteen and devastated, as were we all. This journey had lasted four years, and there was no hospice then. My father put a hospital bed in their bedroom and slept on a single bed next to her every night. For the last three months, we had two shifts of nurses every day.

When she died, my father was left with three shattered children, a broken heart, and a mountain of debt. He had to sell the dream home they had bought after the war. He was a good man, and he turned to hard work to care for us and to pay off the debt. It took him almost fifteen years to pay it off, and I know he had to deal with several threatened lawsuits along the way. During those years, as if the debt was an ongoing reminder of his broken heart, I saw a vital part of his spirit close down and become inaccessible to us. Learning that tragedy and debt can easily combine to sap our spirit and wall off our capacity to be open and loving is a harsh lesson.

Story Number Three

When I was a junior at Georgia Tech, I went to a French-themed party at my fraternity house after a football game. As I walked into the bar area of the party room, I saw a young woman sitting at the bar in a jaunty beret and a sexy black dress with a split skirt. As she talked, she radiated vivacity and humor. When we danced, her eyes sparkled. We were married during my senior year and had our son the week I graduated. Over the next few years, we had two daughters. To tell the truth, we had both experienced anguished childhoods and, in a sense, were lost children who dreamed of creating a perfect family. We worked very hard in that direction. When my wife was in her late twenties, I noticed she was struggling at times with herself and her feelings. But I was working hard and wasn’t very psychologically minded at the time. I suggested she go back to school, and she did.

A few years later, she became almost totally inactive, lying on the sofa most of the day, weeping at times, and pouring her heart into her journals. Our family doctor suggested we see a psychiatrist and gave us a referral. I was stunned, but my wife seemed full of hope that she might be understood and helped. We went into his office where he sat in a coat and tie behind a huge desk. After we relayed to him a brief history, he asked me to leave the room so he could talk with her. As I was leaving, I saw her handing him her journals.

After about half an hour, she came out looking like she had shrunk a whole size. His secretary asked me to go in. I sat down in front of him. He leaned back in his chair and said to me in a gruff voice, “Hell, man, she’s psychotic. She needs to be in the hospital.” Then he tossed her journals across the desk at me and said, “Have you read this stuff? It’s schizophrenic!” Well, to be honest with you, in 1970 I didn’t know what schizophrenic meant. But I had read some of her journals and knew what pain and struggle looked like. What he said temporarily shocked me into immobility, which was good because I would have done him bodily harm for his crass response to me and someone I loved.

However, I followed up on his advice and went to visit the Georgia Mental Health Institute, which was a psychiatric hospital in Atlanta with a good reputation. It was also a teaching hospital for Emory University, which had the reputation of having the finest medical school in the state. The staff was very kind, and they showed me around the hospital, which was actually a group of large cottages (units) connected by underground tunnels and having grassy courtyards. Paradoxically, I actually did an internship there some years later.

The staff explained that their treatment approach was “rapid tranquilization” (common and popular at the time), which amounted to sedating the patients and bringing them under control. I thought to myself that this simply turned their patients into zombies. My wife wasn’t having violent fits, and I couldn’t see putting someone I loved into this situation or kind of treatment. So, I thanked them, left, and earnestly began to look for other options.

This has been the hardest story of all for me to remember and to tell. I find it hard to revisit. My memories are foggy; I don’t want to remember these very hard times.

The following years were filled with pain and struggle. Yet there were many happy moments with my kids. It took me decades to recall that it wasn’t all hell with my wife; there were happy moments with her, too. We eventually found the Atlanta Psychiatric Clinic, which was a cutting-edge clinic of top psychiatrists and psychologists who were deeply versed in a humanistic approach to the human psyche, the soul, and psychotherapy. Even though my wife was diagnosed schizophrenic, drugs were never suggested. We initially went for therapy two or three times per week. The therapy passed the decade mark and went on.

I know our life was very turbulent, scary at times, harrowing at other times, but I believe what we did added years of real living to her life and gave our children a better experience of her than they would have had otherwise. Let me tell you, though, that what made those years seem like a total hell was having my back to the wall financially, day after day, with no end in sight. This damnable pressure robbed me of being able to enjoy our kids in the way I wish I could have, of loving them the way I really wanted to, and of being there for them the way I wish I could have been when they needed me. It also caused me to lose my temper at times that I now regret. Eventually, it all became too much, and I had my own period of collapse which included a divorce.

Story Number Four

In the year 2004, my daughter was diagnosed with progressive multiple sclerosis. Hers was a young family, with three children in the house and a husband who owned his own small business. That year put them on a chilling roller coaster ride that is still continuing. If I tried to describe it, I would choke up and lose my ability to write. But they continue to meet the demands—all of them, with love, courage, and resilience. But what I can tell you is from the day she was diagnosed until the day the Affordable Care Act passed, they were stuck in being unable to change their health insurance. The medical bills that weren’t covered by their insurance ran into the middle five figures, year after year. They were able to change policies after the Affordable Care Act passed, but their monthly premium is still over $3,000 a month, and they still have to pay deductibles and co-pays.

Can you imagine what this kind of financial pressure does to a family when it combines with such a severe illness in a loved member? Ten thousand new cases of MS are diagnosed every year—about 200 per week, and the number is growing. Are we going to continue to abandon our most vulnerable citizens, our loved ones, to a financial hell while they are caught in the relentless undertow of this basic reality of life?

The Rage and the Pain

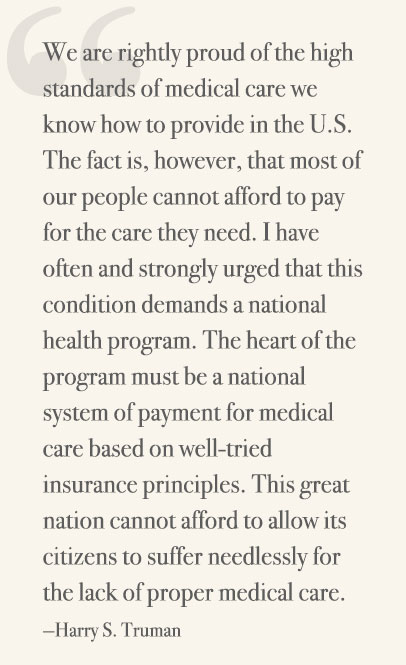

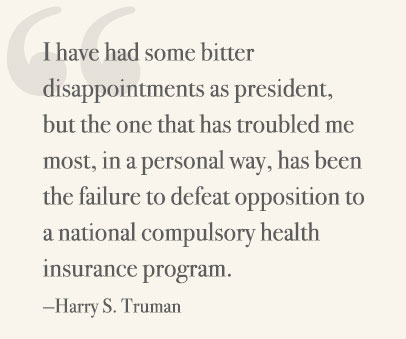

Terrorists rely on making us live in fear of what’s going to happen next. We wait, we expect, we anticipate, and we imagine…and always the worst. Living in the face of a serious illness — where every decision is made based on health needs or governed by costs or by whether the finest doctor is an in-network provider — is another kind of terrorism. I know the terror, and I weep burning tears for the unnecessary suffering of three generations of my family—my parents, my wife and me, and our children—and the millions like us. I say “unnecessary” because President Harry S. Truman, one of our most practical and honest presidents, proposed to Congress a new national health-care act in 1945. Enacting it would have saved all three generations of my family plus millions of other American families from the needless financial crunch that drained too much of our capacity to love and care for each other in some of life’s darkest moments.

I am so angry, angry, angry that words of profanity expressing my anger don’t even come to me. My shadow, my inner deplorable, is wild with the rage I’ve denied at the members of our Congress—sitting there in their cocoons of health-care security for over seventy-three years. For all that time, they have been carrying on about such issues as government interference, deficits, taxes, statistics, and stuff like that while the people in my family, my friends, and many of the people I work with are being crucified on a cross of medical bills, treatment choices, and financial despair that scorches the soul of someone who is trying to cope with some of life’s blackest moments.

Senators and representatives, where are your hearts? But I must also ask, “Where have the hearts been of those who elected you…where has my heart been?”

I am an American and I believe in competition in the right places. We are number one in health costs per capita in the developed nations. But according to the World Health Organization, the U.S. is ranked number thirty-seven in the world for its level of health care and education. Please tell me, Mr. or Ms. Congressperson, what are we competing at here?

I can’t help but wonder why it is so easy for us to lie to ourselves and each other. For example, calling a single-payer system “socialized medicine” is perpetuating a term coined by a major advertising agency that the American Medical Association, fearing change and loss of control of the health-care market, hired to combat President Truman’s proposal. As I said previously, when we follow the road of fear, we generally end up on the road to disaster. In a true socialized-medicine situation, the government pays the bills, owns the health-care facilities, and employs the professionals who work there. Our Veterans Administration health system is a socialized health system run by the government.

Some time ago, a physician client of mine said he felt very guilty because he could afford my services and yet many of his patients who badly needed this kind of help could not. That is part of the very problem I’m talking about. In most developed countries, people’s health plans would cover my services. In general, the term single-payer means that all medical claims are paid out of a government-run pool of money. Under this plan, all providers are paid equally, and patients receive the same benefits regardless of their ability to pay. A single-payer fund can include a public health-care delivery system, a private delivery system, and a mix of the two, such as I have with my Medicare and Medicare supplemental policies. When I lived in Europe, I learned that most European countries had a wide range of supplementary policies one could buy, similar to the wide range of Medicare supplemental policies I can buy through private companies here in the U.S.

A shameful part of our Medicare history has been that Congress reserves the right to limit provider fees. Too often it seems to me they have kept the fees low as a political manipulation to turn providers against the system. Another shameful aspect of this problem is that we fail to educate ourselves and our American family about what a single-payer program really means. It ensures access to medical care for everyone. This fact alone means that the prevention of disease and the promotion of healthy living will have a major focus. It means, and tears well up when I think of this point, that the fear of medical bankruptcy or of making a wrong decision because of finances or simply living in financial terror might no longer be an issue.

A big part of the shame is the lies we are told and the lies we believe that come from people with a vested interest, such as insurance companies and their lobbyists. The for-profit health-care industry is quick to tell us we will lose the freedom to choose our plan and to choose our doctor. Well, guess what? We lost those freedoms long ago. What if the doctor or specialist you want is not on your insurance company’s network provider list? This happened to my daughter. As for choosing your own plan—if you have an employer, that’s done for you and generally to your employer’s advantage. Anyone naïve enough to think that buying a plan on an open competitive market is a good idea should take a look at all the complicated medical terms, legalese, and exclusions in every plan. Thinking the average American could make an informed choice on the open market is simply a cruel joke.

There are almost too many lies perpetuated in our national debate on health care for me to even discuss. “Death panels” were a lie. Another lie is that care will deteriorate or cost a lot more. Really? Remember, we are already thirty-seventh in care but first in costs—far ahead of all the other countries that have single-payer plans and better care than us.

* * * *

Even as I finish my reflections, I have to ask myself these questions:

- Wouldn’t it be better if we face the truth that we, the majority of our citizenry, want to stop the financial horror that accompanies illness in this country and adopt a single-payer system?

- Wouldn’t it be better if everyone with a disease or illness is treated, and prevention and healthy living are promoted?

- Wouldn’t it be better if we challenge ourselves to become the number one country in the world in health care?

- Wouldn’t it be better to be the world’s leader in promoting an environment that doesn’t make us sick?

The Bedrock of Cruelty

It is incredible how deaf, dumb, and blind we are to nonphysical pain. If you break a leg, have cancer, the flu, or some other disease, people sympathize and want to help you. They show you respect. If you are in an area where a hurricane has trashed everything, people rush in with boats, food, shelter, and all sorts of help. But if you are paralyzed with despair, scared to get out of bed, can’t see a reason for living, have lost hope, or are just sinking into a swamp of bitterness and misery, it almost seems like no one can help you—or in fact really wants to try to help you. Plus, our addiction to positive thinking enables wholesale denial of the amount of psychological suffering around us, and perpetuates our view of it as a personal, embarrassing, and humiliating failure.

And, you may be sure that seeing how much the profession I entered with enthusiasm, hard-earned educational credentials, and the hope to make lives better has been marginalized fills me with the kind of anger that better helps me understand other angry people in political rallies. Perhaps we are angry at a society we feel has marginalized us.

Statistics tell us that on average, 129 of our fellow Americans kill themselves every day. An estimated 88,000 die of alcohol-related causes every year. There were more than 70,000 deaths from drug overdoses in 2017. My daily news sources bombard me with the severity of the opioid crisis we are now having throughout our country.

I believe there is an important story behind these statistics. When I did much of my training during the 1970s and early 1980s, a lot of attention was being given to mental health and treatment, and to the dramatically increasing rate of depression and anxiety in our country. Mental health was well covered by insurance plans in the 1980s, and it was recognized that every dollar spent on mental health saved three dollars in other medical, law enforcement, and social costs.

When I and my current wife, who is also a Jungian psychoanalyst, moved back to America in 1989 after our analytic training in Zurich, Switzerland, we chose to live in Asheville, North Carolina. Asheville is a beautiful mountain town that I had been familiar with since childhood, and I had always seen North Carolina as a progressive state (I don’t mean in current political terms, but in reality). When we arrived here, we found a very active state-supported mental health system. The offices in Asheville were welcoming and well-staffed by psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and supporting staff. Counseling and therapy were available for adults, couples, families, adolescents, and children on a sliding scale depending upon income. This system was supported by two private psychiatric hospitals in the city, two solid addiction treatment programs, and a supporting network of private practitioners. My wife and I were glad to join this climate of professionalism and caring.

By the year 2000, all these facilities were gone—the state facilities, the psychiatric hospitals, the addiction treatment programs, and many of the supporting professionals. What happened to these programs fills me with a cold rage—a rage that eliminates my detachment and any chance of forgiveness. Where did they go, you might wonder? The answer is that “managed care” came on the scene. Under the rubric of cutting medical costs and delivering “better care,” the true focus was on increasing profits.

Too many people have bought the illusion that therapy or counseling shows weakness and that all it consists of is vomiting one’s feelings. These are destructive fictions. North Carolina’s former facilities had the purpose of helping people to build a foundation for living productively and responsibly, to build skills, to break out of loneliness—which our research shows kills us. Those mental health systems were meant to help citizens find hope, direction, and the capacity to love, and to make a contribution to society. They were meant to express our caring for each other and our compassion for the truly mentally ill so they could live in dignity, and their families could live securely.

The reality was this. If some man or woman was drowning in despair, anger, or confusion, if some teenage boy or girl was struggling to stay afloat, or some couple or family was caught in the riptides of modern life, if someone was caught in a hurricane of addictions, there was a safe harbor—a place to find care and support. Such a harbor gives support to the whole community. It gives parents, teachers, ministers, and even the police a feeling of security that facilitates empathy, caring for each other, and civility. It does so because we know our backs are covered if we pay attention, listen to each other, and get involved.

Because they address nonphysical pain that people prefer to be blind to, mental health benefits were an easy area in which to start cutting costs. Using the “managed care” method, the health insurance companies made getting treatment approvals so limited, so tedious, and so obnoxious that our delivery system buckled, and many of our best providers either quit taking insurance or left the field altogether while our politicians, professional associations, and the media turned a blind eye to what was going on. The public simply focused on the illusion that things were getting better and tried to appear happy, an approach to life that fosters denial. (Once again, check out Barbara Ehrenreich’s Bright-Sided.)

Our mental health care system is very broken, and we have lost a critical support system that we badly need in a culture that is being driven by fear, anxiety, and anger. I have kept too much anger locked inside of me. I am very angry that so many people in this new opioid epidemic really have no place to go for help. I’m even angrier that all the places they could have gone to for help or treatment to ward off the pressures or problems that lead to addiction are simply no longer here. And I am ashamed of our politicians, and I am ashamed of all of us for letting this cruel tragedy happen in our society.

* * * *

When I began my professional training in psychology in the early seventies, the atmosphere of the field was still dominated by the work of the great humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers. He was a man whose work was governed by depth and kindness, including his groundbreaking book Becoming a Person. Rogers taught that to become a person, we must know ourselves. We must confront and know our shadow, our darkness, our rage, and our shame. And we must know the goodness and strength within ourselves that we have repressed, because to have lived them would have made us different from the crowd—noticed, embarrassed, perhaps even criticized. But we must face these parts of ourselves and learn from them. It is only from this foundation that we can live into the realizations of truly new potentials, restore old worlds, and recognize new horizons. Becoming a person in this way is also the best foundation for becoming a good citizen, a person who acts responsibly to nourish and energize our government as one of the people, by the people, and for the people.

I pray that we can face our cruelty as our forebears faced their darkest hours and find again America’s strength. This strength has been our ability to stand up to any challenge, no matter how difficult and daunting. Isn’t it time that we accept our challenge to create the number one health-care system in the world, one that considers and treats every citizen as sacred?

The above is Chapter 10 of my book The Midnight Hour: A Jungian Perspective on America’s Current Pivotal Moment.

The above is Chapter 10 of my book The Midnight Hour: A Jungian Perspective on America’s Current Pivotal Moment.

BUY FROM YOUR LOCAL INDEPENDENT BOOKSTORE

Book Excerpts and Resources

, 2021, America, being human, citizenship, Elder Wisdom, fear, healthcare, hope, living authentically, poverty

2 Responses to “Health Care: Isn’t It Time to Quit Being the Cruelest Developed Nation?”

Please stay positive in your comments. If your comment is rude it will get deleted. If it is critical please make it constructive. If you are constantly negative or a general ass, troll or baiter you will get banned. The definition of terms is left solely up to us.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for your courage to share your stories and for your hope that we might create wiser policies that support and serve all of us. You stories are poignant and inspiring. Thank you.

This is such an excellent article. I wish it could be published in many newspapers and publicized widely. It demonstrates so profoundly the need for immediate wide-spread education and action for single payer health care! So courageous to share your stories and so importantly illustrative of this country’s lack of compassion and intelligence and need for change.