The following is an excerpt from my book Becoming Whole: A Jungian Guide to Individuation.

I think most of us would like to know more about what a complex is, what it does, how we spot it, and then what are the steps we need to take to integrate it into our personality. And this is how I’m going to proceed, beginning with the question—what is a complex. Our complexes come from our deepest human experiences. They begin with how we experience our mother and father. They are formed by the emotional encounters that shape us, usually or most notably the negative and traumatic ones, because growing up is always difficult and a struggle even in the best of circumstances.

If we simply look at the psychoanalyst Erik Erickson’s developmental phases, we see that each one of them is marked by a crisis. The names he has given these crises tell us of their intense and dramatic nature-for example, basic trust versus basic mistrust; autonomy versus shame and doubt; initiative versus guilt; industry versus inferiority; identity versus identity confusion; and intimacy versus isolation. Every step in growing up presents a major challenge and the potential of a trauma that can cause a whole village of complexes to develop. Many of these complexes form to protect our vulnerable child-self from shame, guilt, trauma, fear, or some other overwhelming emotion. Complexes can also result from injunctions like “Don’t be stupid. Do it yourself. Please your parents. Please your teachers.” And this doesn’t even get us into the big stuff like violence, abuse, illness, loss of a parent, or having disturbed parents.

Complexes that will affect our lives generally have to do with relationships. The way others respond to us, as we grow up, shapes our view of ourselves and the world. Once we awaken to a complex, we face a task—a journey—yet this journey isn’t back to normal, for in Jungian terms there is also a promise. The promise of the journey is to have an enlarged life of increased empowerment and authenticity; and if this complex is a central or dominant one—a destiny. If you read my first book, now re-titled The Resurrection of the Unicorn: Masculinity in the 21st Century, you can see behind the pages, my personal story of working through my mother complex and then into the full meaning of being a man.

The promise in a complex comes from its archetypal foundation. Archetypes are the psychological blueprints in our makeup for how our experiences and emotions can be channeled. Let me read to you what Jung says about the archetypes in his essay, “The Significance of the Father in the Destiny of the Individual.” (C.W. 4)

Man “possesses” many things which he has never acquired but has inherited from his ancestors. He is not born a tabula rasa, he is merely born unconscious. But he brings with him systems that are organized and ready to function in a specifically human way, and these he owes to millions of years of human development. Just as the migratory and nest-building instincts of birds were never learnt or acquired individually, man brings with him at birth the ground-plan of his nature, and not only of his individual nature but of his collective nature. These inherited systems correspond to the human situations that have existed since primeval times: youth and old age, birth and death, sons and daughters, fathers and mothers, mating, and so on. Only the individual consciousness experiences these things for the first time, but not the bodily system and the unconscious…

I have called this congenital and pre-existent instinctual model, or pattern of behaviour, the archetype.

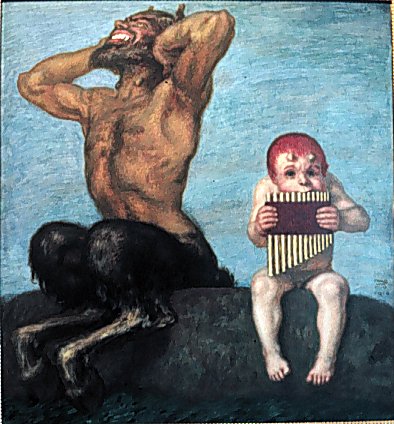

Archetypes are like hidden magnets in our psyche that attract and pattern our experiences and emotions. For example, if my father is bombastic, aggressive and shames me for being timid and quiet, I will find my emotions defensively patterned by fear into withdrawal, and the reluctance to express myself. On a deeper level, I will have anger and resentment for his failure to value and understand me. I will have developed a negative father complex. That complex will flood me with fear, confusion, anger and resentment whenever I encounter a bombastic or aggressive authority figure.

But every archetypal image has two poles. The negative father has its opposite, the positive father. The unrealized potential of the opposite pole offers the possibility for growth and transformation. The complex provides the link between the archetypal potential and our ego (our sense of who we are). In other words, when we do the work of integrating a complex, who we think we are is radically transformed. Our ego, our personality has found new strength and emotional balance. We will begin looking at how to integrate a complex in Part B of the lecture.

In summary, a complex is a storehouse for the intense personal emotions we experienced around an event or series of events that are connected to a typical pattern of development or activity in our personality. The complex will cause us to act in ways that protect us from these emotions. Its potential for growth lies in its call to us to heal our past, release the energy the complex is costing us and experience the new growth that is now possible.

Buy Paperback from Malaprop’s Bookstore

Art credit (painting above): Dissonance, Franz Stuck

Book Excerpts and Resources

, authenticity, Carl Jung, Jungian psychology, Personal Transformation, psychological complex

Please stay positive in your comments. If your comment is rude it will get deleted. If it is critical please make it constructive. If you are constantly negative or a general ass, troll or baiter you will get banned. The definition of terms is left solely up to us.

Leave a Reply